Why Cancer?

by Julia Vassey

Dr. Catherine Metayer can recall the most challenging moments of her medical career vividly – they came during those harrowing times when she had to deliver patients the bad news.

“I felt it was such a challenging experience when you are being told that you have cancer. It triggers such an emotional and stressful time for you, for your family,” says Metayer.

The first question on the mind of a newly-diagnosed cancer patient is often “why did this happen to me?” Metayer didn’t always have the answers.

Born in France, Metayer has been fascinated with medicine since the age of 13, when she learned of the discoveries of her famous countryman, biologist Louis Pasteur – a pioneer in disease prevention who developed the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax.

But it was cancer that intrigued her most. In the 1990s, she became a resident in oncology and pediatrics and worked at hospitals in the Bordeaux region of France.

Metayer was troubled by those “why me?” experiences with her patients. To find the answers they were looking for, she quit her job in France and left the country to pursue a career in cancer epidemiology in America – the “land of opportunities” for learning about advanced cancer research.

Her personal American Dream was elusive at first. While working on her PhD in Epidemiology at the Tulane School of Public Health in New Orleans, she was just trying to “get by with her poor English,” says Metayer.

She arrived at school well prepared each day, but never uttered a word in class.

“In spite of that, I noticed soon that Americans were welcoming and ready to give me a chance,” she says. “Back then, not so many physicians were seeking a degree in public health, so my contribution was valued and encouraged.”

Metayer studied the immune system’s defense mechanisms against cancer, and was trying to figure out if viruses could trigger leukemia in adults.

After completing her PhD, she joined the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, MD, to study patients with secondary cancers.

Soon after joining the institute, Metayer found a mentor. Patricia Buffler – a professor and former Dean of the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley – was visiting Bethesda to give a presentation about her search for the causes of childhood cancer, a topic that had been on Metayer’s mind since her days as resident. The two researchers quickly connected, and Buffler brought Metayer on board her research group in California.

In the Middle of CIRCLE

When Metayer came to Berkeley, most of the world’s cancer research was still focused on adults. Very little was known about the causes of childhood leukemia. Metayer wanted to change that.

So she and Buffler created the Center for Integrative Research on Childhood Leukemia and the Environment (CIRCLE), a Children’s Environmental Health Center jointly funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Environmental Protection Agency. After Buffler’s death in 2013, Metayer carried on their work, assuming the role as the leader of the Center.

“A huge gap in understanding why children have this type of cancer still exists,” Metayer says.

Under Metayer’s direction, CIRCLE researchers have been studying unhealthy lifestyles (like cigarette smoking and poor diet), exposure to environmental chemicals (from pesticides, to paint, and air pollution), and prenatal factors (like fetal growth and maternal stress) – which may damage a child’s DNA or alter her immune function possibly leading to cancer.

The scientists have found that exposure to the environmental chemicals accounts for about one-fourth of all childhood leukemia diagnoses. “This is not negligible,” Metayer says.

CIRCLE research also showed that healthier maternal nutrition and folate supplementation with a prenatal vitamin can protect against leukemia, contributing to normal development of the child’s immune system.

Because the disease can start during pregnancy or even before conception, CIRCLE uses an innovate approach to examine chemical exposures that may have emerged prenatally. The center takes samples from newborn dried blood spots that are routinely collected and stored by the State of California to screen infants for genetic disorders. CIRCLE studies showed that paternal preconception smoking was associated with the increased risk of childhood leukemia.

Orchestrating International Collaboration

Leukemia is the most common type of childhood cancer, but it is still a relatively rare disease. Every year in America, about one-and-a-half million adults are diagnosed with cancer, while fewer than twenty thousand children get the disease. Studying a rare disease like childhood leukemia poses methodological challenges for Metayer and her center.

“Our research always goes through a very stringent peer review,” says Metayer. The small number of sick patients available for participation means her studies tend to have small sample sizes, which can draw skepticism from reviewers.

To overcome this problem and make the findings more credible, ten years ago, Metayer and Buffler decided to expand the pool of patients and look at the global experience with childhood leukemia.

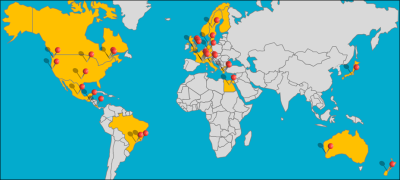

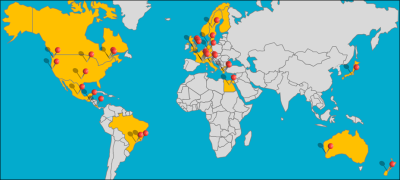

The CIRCLE researchers brought together a team of international collaborators – from France, Canada, and Australia – who were asking the same research question as CIRCLE: what are the causes of childhood leukemia?

“So we sat down and asked ourselves what would it take to work together,” says Metayer.

The researchers decided to form the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium (CLIC) where members would pool data from their individual studies to learn more about the risk factors for childhood leukemia and help develop strategies to prevent future cases of the disease.

Within a decade, the scope of CLIC’s research has grown from four studies to 30 with 40,000 leukemia patients now enrolled around the world.

Metayer, who is the chair of the consortium, says that the CLIC researchers really “clicked.”

At times, Metayer feels like a “conductor” leading an orchestra of investigators. Each player has a part and together they are creating a symphony. The rich variety of data, brought together from different countries, brings more insight and helps researchers decipher the true triggers of childhood leukemia.

“The scientists volunteer for the consortium. They are very motivated. They work out of their hearts” to share resources and expertise, says Metayer.

The great success of the international consortium is among Metayer’s brightest career highlights.

Leukemia in Latinos

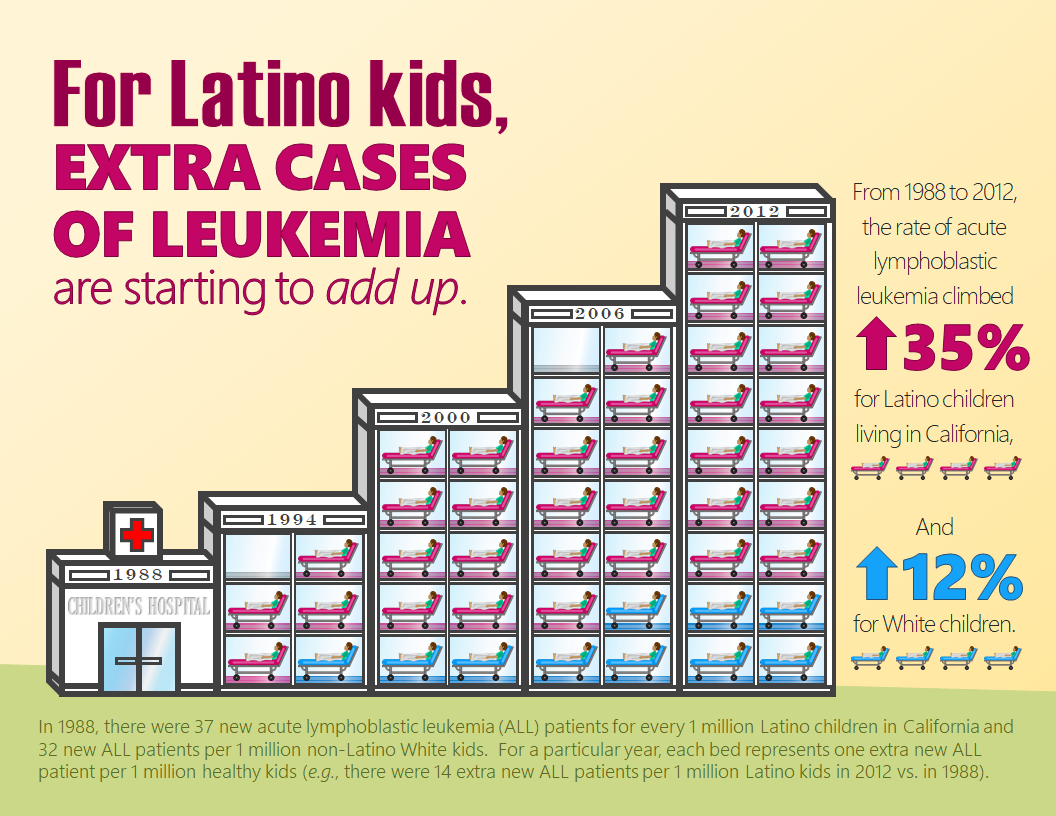

Rates of childhood leukemia are on the rise in the U.S., especially among Latino children. In California, the number of Latino kids with acute lymphoblastic leukemia has increased by 35 percent over the past 40 years.

The reasons for the rising rates are not well understood, but CIRCLE researchers have some leads. Latinos in California can face work-related health hazards. CIRCLE researchers discovered that Latino children whose fathers are exposed at work to chlorinated solvents – well-established carcinogens in adults – are at higher risk of getting leukemia. “Because solvents are highly volatile and quickly dissolve, we think that they impact the father directly by damaging his sperm cells before conception,” says Metayer.

But the discovery of the effect from solvent exposures brought an array of other questions: “Why only Latino fathers? Do they have different work habits?

Are they exposed to higher levels of those chemicals? How well do they use protection equipment? Is there an issue about genetic susceptibility when the body breaks down those chemicals?” Metayer wonders.

Pesticides exposure is another problem uniquely affecting Latino communities – one that the CIRCLE researchers are paying close attention to. In California, 75 percent of the workforce in agricultural fields is Latino. These workers are constantly exposed to pesticides. Accidental inhalation of the sprayed chemicals is common.

To make matters worse, farm workers may track pesticides home on boots and clothes, exposing their children to toxic chemicals.

Research from CIRCLE and CLIC investigators has consistently demonstrated that residential pesticide use during pregnancy can increase a child’s risk for leukemia, but these troubling findings are sometimes overlooked.

Next to adult cancers, asthma or autism, leukemia research that the CIRCLE center is focused on is “just a little drop in the ocean for regulators and funders,” says Metayer. That’s why pushing regulating agencies to put restrictions in place for the use of certain environmental chemicals has always been a challenge.

Life After Leukemia

Since the 1990s, the quality of leukemia treatment has significantly improved and the survival rate has increased, but the consequences of childhood leukemia remain a heavy burden. Long-term and secondary effects that often appear later include diminished neurocognitive development, depression, and obesity.

While continuing her quest for what triggers the disease, Metayer’s new aspiration is to look at children-survivors who have undergone cancer therapies.

The researcher says a lot of effort has been put into studying the side effects of cancer therapies, but little attention has been paid to the lifestyle and environmental exposures of patients after cancer treatment.

According to Metayer, many survivors – mostly Latino children – experience increased rates of obesity and neurocognitive disabilities that could also be explained by poor diet and the presence of toxic chemicals. Children who survive leukemia – especially those living in poor conditions – are potentially exposed to neurotoxic substances like flame retardants, air pollution, and lead.

“I want to bring the world of environmental health to cancer survivor studies and find out whether the environmental impacts those long-term sequelae of leukemia,” says Metayer.

Metayer is actively pursuing funding to support this next phase of her research.